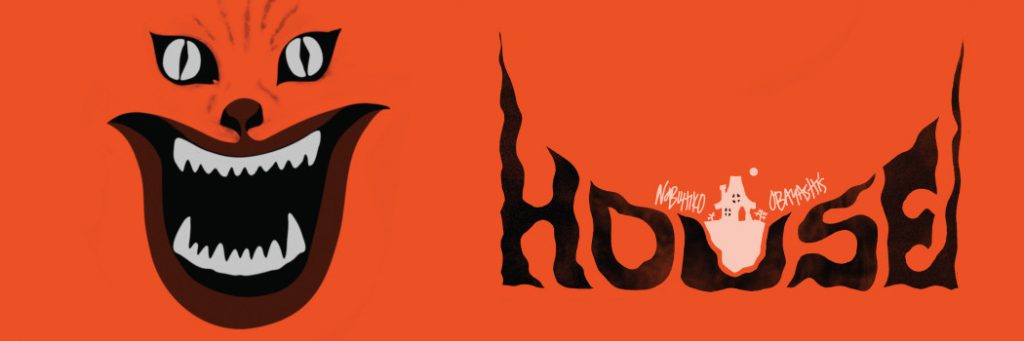

I feel that a lot of the time, Japanese movies aren’t viewed fairly by Western audiences. There seems to be a pervasive idea in the West that Japan is weird and crazy, and the movies the Japanese people produce are largely the same. This thought process is especially apparent for movies which fall into genre categories such as horror. I don’t think people necessarily see this as a negative stereotype, and in fact, one of the things that draws many people to Japanese cinema is the fact that it is perceived to be so strange. But even though I wouldn’t presume to tell someone that they like something for the wrong reasons, I do think applying the “wacky Japanese” label to a movie inevitably leads to superficial and dismissive readings of that movie regardless of any depth of meaning or quality of craftsmanship involved. Such is the case with the overtly wild and deceptively brilliant Japanese horror classic from 1977, House.

If you search online for opinions on House, you’re going to find a lot of rave reviews. The praise is well-deserved, but when a large portion of the reviews simply say the movie is “insane,” “crazy,” and even “incomprehensible” as the main reasons why you should watch it, I think a lot of the reviews miss the point. Yes, the visuals in House are wild and unlike most other movies, but there’s so much more to House than its craziness. It is a well constructed horror movie which gleefully embraces the film medium and pushes it to ridiculous extremes in the best and most intelligent ways. But maybe I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

House is the story of a high school girl, the appropriately named Gorgeous, and her six friends who journey to the countryside to stay at the house of Gorgeous’s aunt for their summer vacation. As soon as the girls step inside the large and suspiciously dilapidated house though, their vacation takes a turn for the strange. Inanimate objects begin moving on their own, the girls begin disappearing one by one, and there’s something rather odd about Gorgeous’s aunt. The movie quickly ramps up the action with a combination of practical effects and multiple types of visual effects to create a surreal and dizzying viewing experience that builds to a blood-drenched climax which can’t be adequately described through words alone. House the the type of movie that you must watch and experience, and it’s definitely an experience you won’t forget.

But with that description, how am I praising House for any reason other than its admittedly wild visuals? Well, I think the visuals are just one part of why House is a masterpiece. The film’s depth goes way beyond its brightly-colored surface, all the way back to classical Japanese ghost stories.

The basic story at the heart of House feels very much like a kaidan, the collective term for ghost stories that originated in the Edo period of Japan. These stories have had a strong influence on Japanese horror cinema, and House is no exception. When I first watched House, I was immediately reminded of classic Japanese ghost movies like Ugetsu (1953) and Kuroneko (1968), two films that were clearly inspired by kaidan. Without spoiling any of the stories, all three movies feature similar structures involving a vengeful spirit of someone who was wronged in life and now preys upon unsuspecting people in a mysterious and ghostly house. The manner in which these stories develop and the ways they are resolved are all very similar and have roots in Japanese folk tales. So in a very clear way, House is a quintessentially classic Japanese ghost story.

At the same time though, House is incredibly modern. Part of this feeling of modernity has to do with the way in which director Nobuhiko Obayashi manipulates the very medium he uses to tell his story. While most films attempt to establish a suspension of disbelief in the viewer through a continuity of seamless edits and natural-feeling transitions, Obayashi makes it very clear from the very first shots of House that we are watching a movie. The first shot of the film is of Gorgeous. She is dressed in a white white wrap of some sort and is having her picture taken by her friend, the equally appropriately named Fantasy (she like to take pictures and is the dreamer of the group). The image we see is monochrome and smaller than the full height and width of the screen. After the photo is taken, a full-color background appears behind the smaller image as Gorgeous removes the costume she was wearing. Gorgeous then steps to the side, meeting the background image and becoming part of it. The illusion of the photograph is broken, and we see that Gorgeous is a school girl and she was in a classroom all along.

This kind of unconventional visual style is used repeatedly throughout the movie, reminding us at all times that we are watching a movie. We are watching something that isn’t real, but is a heightened version of what reality can be. This technique not only allows Obayashi to get away with many things that other filmmakers wouldn’t dare to attempt, but it also allows Obayashi to add layers of information into every shot of his his movie, layers that other directors wouldn’t have access to. It also has the added benefit of conditioning the viewer to be more receptive to the increasingly bizarre images we experience throughout the film.

In addition to the visual effects, another way in which viewers are conditioned to accept some of the unbelievable events we see is through the choices Obayashi makes in set design. While there are a few scenes which are shot in natural locations, the overall feel of the movie is that it is filmed on a set. There doesn’t seem to be any real attempt to make it feel as if these sets are real locations either. For many outdoor scenes, the background is very clearly a matte painting, and the same matte paintings sometimes seem to get used for multiple locations. The best example of this occurs in the scene when the girls are journeying to the countryside.

First, we see the girls in front of what is obviously a painting of a train station. We see a car drive up to it though, so we are meant to accept that this is indeed a real train station in front of real skyscrapers and real clouds. From this we cut to a shot of the girls passing in front of an outdoor scene. As we pan to the left we realize that these clouds are not real, they are painted on a wall inside the train station. Then, we see the same painting of clouds again as the girls board the train. We see it a third time when the girls reach their destination, but here we cut to a wide shot and realize again that these clouds are fake. Behind them are the real clouds, which are, of course, another large matte painting. It’s this kind of misdirection and not-so-subtle blurring of reality and fantasy that help us accept it when we see a dancing skeleton or a laughing watermelon later on.

Viewers aren’t the only people that seem to be aware that we are watching a movie though. The girls themselves seem to be aware of this on some level. In one sequence while Gorgeous is telling her friends the story of her aunt, the flashback is presented in the style of a silent film complete with intertitles. Gorgeous narrates the story, but the girls are clearly watching the film along with us and commenting on the things they see, not the things they are told. The girls even read the intertitles along with us, at one point commenting on how one of the girls misreads one of the kanji on screen. But even though the girls are aware of watching a non-existent film of a flashback, they don’t see this as unusual and they never break the fourth wall in their own story. This is yet another way in which Obayashi blurs fiction and reality, making the bizarre an acceptable part of the world he has created.

And I think that’s really the point I’m trying to get across here. House is a strange movie, yes, but it is very clearly designed for a specific purpose. None of the crazy visuals or story elements are done haphazardly. They are all there for a reason. What might appear to some to be a mish-mash of incoherent scenes is actually a cleverly crafted work of art. The movie definitely has a deeper meaning than many of the reviews would lead you to believe. It’s a ghost story, but it’s also about growing up in a country affected by war. It’s about womanhood. It’s about family and marriage. It’s about all of these things, and all of these themes are woven into the over-the-top visuals we see on screen.

Rating

9 – Great

I think everyone should watch House at least once. Really, considering how overwhelming it can be the first time, maybe everyone should watch it at least twice. You might come away thinking it’s just crazy fun, and that’s okay. It is crazy fun. But it’s so much more than that at the same time. It’s the product of centuries of folklore, decades of film history, and years of cultural development, told in a frenetic fever-dream of a movie. And I think it’s brilliant.

For more of me gushing about this film (and attempting to explain the points I only begin to uncover here), check out episode 3 of The Last Theater on the Left podcast!

LTL Podcast Episode 3: House

RECOMMENDATION FOR FURTHER WATCHING

Kuroneko (1968)

Kuroneko and House are very similar to each other at their most basic level and both continue the tradition of classical Japanese ghost stories. Though, Kuroneko is presented in a traditional way while House most definitely isn’t. I think watching these two films back to back would be an interesting double feature. I think you would see many similarities, not the least of which being a creepy cat at the forefront of both films.

Kuroneko and House are very similar to each other at their most basic level and both continue the tradition of classical Japanese ghost stories. Though, Kuroneko is presented in a traditional way while House most definitely isn’t. I think watching these two films back to back would be an interesting double feature. I think you would see many similarities, not the least of which being a creepy cat at the forefront of both films.

DETAILS

Title: House

Japanese Title: ハウス (though, House in English is the official title even in Japan, this is merely the Japanese pronunciation)

Japanese Title (romaji): Hausu

Year: 1977

Director: Nobuhiko Obayashi

Writer: Chiho Katsura

Featured Cast: Kimiko Ikegami, Miki Jinbo, Kumiko Oba, Ai Matsubara, Mieko Sato, Eriko Tanaka, Masayo Miyako, Yoko Minamida

Run Time: 87 minutes

Availability: DVD, Blu-ray, VOD

One thought on “House (1977) – Review”