For a while now, I’ve wanted to broaden the scope of The Last Theater to include more genres than just horror. I’m a huge fan of all sorts of genres, and for very long time I’ve been wanting to write more about genre films from around the world. Specifically, I’ve wanted to explore East and Southeast Asian genre films in more depth. With that in mind, I’ve decided to go ahead and start a new sub-section of The Last Theater where I’ll analyze, review, and learn about these movies, and I’m starting here by posting a paper I wrote while studying Japanese films in college. I got into the films of Suzuki Seijun (among many other Japanese directors) while in school, and Branded to Kill ranks high among my favorites of his work. So here, I present to you, an analysis of Suzuki Seijun’s Branded to Kill, focusing on a particularly memorable and thought-provoking scene.

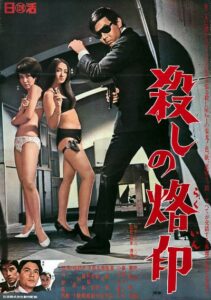

Branded to Kill (1967) is a movie that in many ways defies explanation. Or rather, it is a masterpiece of style that willfully defies conventions in ways that can be difficult to explain. It is a yakuza film as told by a man who was pushing against the limitations set by the film studio that employed him if for no other reason than to create the most entertaining movie he possibly could. That man is director and auteur Suzuki Seijun, and Branded to Kill would be the film that pushed his employers at the Nikkatsu film studio to fire him in 1968 for making “incomprehensible” movies5.

When viewed in comparison to many of the other, more standard genre films that Nikkatsu was pumping out at a rate of about two per week in the 1960s2, Branded to Kill certainly stands out. Its unrestrained experimental style and loose, at times lyrical approach to plot structure can be off-putting for someone looking for a straightforward yakuza potboiler, but a closer (and repeated) viewing of the film reveals a masterful design that uses the well-known conventions of the yakuza genre and film noir as a foundation on which to build a stylish and compelling experience for the viewer. One sequence in particular that conveys all of Suzuki’s stylistic intentions is when the film’s “hero,” Hanada, enters into a life and death struggle with the mysterious and alluring Misako.

When viewed in comparison to many of the other, more standard genre films that Nikkatsu was pumping out at a rate of about two per week in the 1960s2, Branded to Kill certainly stands out. Its unrestrained experimental style and loose, at times lyrical approach to plot structure can be off-putting for someone looking for a straightforward yakuza potboiler, but a closer (and repeated) viewing of the film reveals a masterful design that uses the well-known conventions of the yakuza genre and film noir as a foundation on which to build a stylish and compelling experience for the viewer. One sequence in particular that conveys all of Suzuki’s stylistic intentions is when the film’s “hero,” Hanada, enters into a life and death struggle with the mysterious and alluring Misako.

Like many classic noir anti-heroes, Hanada, played by the puffy-cheeked B-movie star Shishido Joe, is a flawed character who is caught in a trap of danger and obsession. He is a hitman who finds himself fighting to survive after a botched hit makes him a target of the yakuza. Misako, the enigmatic woman whom Hanada first meets by chance after his car breaks down, is the first person Hanada runs to after his treacherous wife tries to kill him on behalf of yakuza boss, and her lover, Yabuhara.

Just as Hanada fits the description of a classic noir anti-hero, Misako perfectly fits the role of the classic noir femme fatale. Played by Indo-Japanese actress Mari Annu, Misako is exotic, seductive, and deadly. Misako is the person who hired Hanada for the job that went badly, a job that he took against his better judgment simply because he couldn’t resist her. She is both the catalyst for Hanada’s descent and the object of his obsession, the very model of a “femme fatale.”

The pairing of Hanada and Misako is a classic combination of character types and motivations that would be instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with film noir or the plethora of yakuza movies that Nikkatsu was putting out at the time. It’s the familiarity that audiences had with the staples of the genre that allowed Suzuki to take some narrative shortcuts. For example, Suzuki doesn’t take a lot time to explain the nature of Hanada and Misako’s relationship or why Hanada is so obsessed with her. A lot of the typical exposition one would expect is left out, so what we see when Hanada first arrives in Misako’s apartment is a fairly condensed version of what might otherwise be a long, drawn out sequence of passion and betrayal. Instead we see Hanada pull his gun on Misako twice, demand that she take her clothes off, nearly get killed by Misako’s poison needle, then demand food from her. All of this happens in less than a minute, and it doesn’t seem out of place because we expect these characters to act this way.

The narrative shortcuts that Suzuki uses also give large portions of Branded to Kill a dreamlike quality. In an interview conducted in Los Angeles in 1997, Suzuki explains that he doesn’t believe that there is any sort of “cinematic grammar.” He explains this to mean that, at least for him and his films, there is no need to establish a fixed time and space1. This approach is especially apparent in the dangerous tryst that Hanada and Misako have. Immediately after demanding food from Misako, Hanada is seen in the background at a table while Misako is framed in the foreground facing away from him. Then we suddenly see Misako facing a birdcage and Hanada is standing. The next shots show Misako facing Hanada as he stands behind a group of dead butterflies that seem to be suspended in midair. All of these movements through space could indicate jumps in time, but they all take place while Hanada and Misako are having a sparse yet linear conversation. These movements through space continue throughout the entire sequence, all the way to when, after sleeping with Misako, Hanada ends up leaving her and running out into the night. It’s unclear how much time has passed, but it feels as if we’ve experienced an entire relationship come together then fall apart, all within the span of about nine minutes. In a way, Suzuki’s refusal to adhere to a traditional cinematic grammar in this sequence feels something like the experience of remembering a past relationship. You only remember the very best and worst parts, and everything else, everything unimportant and everything that connected those parts, simply fades away.

Suzuki’s approach to the tropes of noir and yakuza films also leaves a lot of room to focus on some of the more humorous aspects of his work such as the satire that is ever-present in Branded to Kill. Even without much exposition, the audience is inclined to simply accept the relationship between Hanada and Misako because that’s just what happens in these types of movies. In a bit of humorous self-awareness, Misako seems to be completely aware of what Hanada is feeling, what he’s going to do, and what her role is as a femme fatale. She completely understands the power she has over him. As Hanada contemplates whether to kiss, kill, or avoid Misako entirely, she whispers “I love you” to her caged birds. Hanada, thinking that Misako is mocking him, proclaims that he could kill her at any time. Misako responds by confidently telling Hanada that he won’t do that until he’s satisfied his lust for her. Seemingly caught with no response, Hanada simply curses himself and changes the subject because he knows she’s right. The audience knows too, and explicitly highlighting the stereotypical roles that the characters play by Misako herself is just one way that Suzuki keeps things fresh and funny in a well-tread genre.

Misako is not Hanada’s only obsession though. In what is one of many odd quirks that the characters in Branded to Kill have, Hanada is obsessed with the smell of boiling rice. Suzuki has said that the character trait was simply meant as a way to show that Hanada is Japanese, saying that since he is Japanese he would naturally prefer the smell of rice over something like a steak1. In another interview on the Criterion Collection release of the movie, Suzuki and assistant director Masami Kuzuu say that the idea came from the need for product placement for a rice cooker4. Whatever the case may be, Suzuki’s words indicate that he is more concerned with the practicalities of getting a film made and making it entertaining, but it’s interesting how even a small, seemingly innocuous part of the movie can come to mean much more than it might have been intended to.

Hanada’s obsession with the smell of rice, for example, becomes associated with arousal early in the movie. Upon returning home after meeting Misako for the first time, Hanada is seen thinking about her while hugging a boiling rice cooker to his chest. He then engages in an extended romp around his house with his almost always nude wife. His escapades with his wife are animalistic and violent, and by the way he covers her face, he is obviously thinking about Misako. He hardly seems satisfied as he lays face down on the floor afterwards, but he quickly goes right back to wrapping his arms around his rice cooker. The look of contentment on his face as he breathes in the vapors seems to indicate that the only time Hanada is ever truly satisfied is when he is lost in the steamy embrace of boiling rice. This symbolism is strengthened during his stay with Misako.

When Hanada begins his brief affair with Misako in her apartment, his first demand is that she take off her clothes. When she refuses by waving a poison needle in his direction, a distraught Hanada demands that she make him some rice. She gives him something else to eat, and Hanada’s frustration is clear as he gesticulates and yells from the table. Then again, after Misako calls him out on his desire for her, Hanada angrily demands that she make him some rice. Whether Hanada realizes it or not, it’s as if he is using code to demand that Misako give in to his sexual desire.

Misako also has some recurring elements surrounding her character that wind up possibly representing more than what Suzuki originally intended. When Hanada finds Misako right before they go to her apartment, she is standing on the other side of a fountain, partially obscured by the water. The sound of the falling water continues as Hanada and Misako are transported to her apartment, and one of the first things Misako does is to use a shower to wash away some of blood from the wound Hanada’s wife inflicted on him. This could be seen to symbolize that Misako, represented by the water, is washing away the harm done by his wife.

Suzuki himself might disagree with the symbolic meaning of Misako’s repeated association with water. In an interview discussing his film Youth of the Beast, Suzuki says that the wind used in a pivotal scene had no specific meaning behind it. He says that “there are three ways, all using natural elements, to make a film interesting: one is wind, two is water, three is snow”3. While it is certainly possible that it wasn’t Suzuki’s intention to add a layer of artistic meaning to the water in Branded to Kill, his calculated use of water as a motif makes it difficult to accept his explanation at face value. It is also entirely possible that Suzuki would simply rather allow viewers to determine any additional layers of meaning for themselves without any outside guidance. Either way, it’s difficult to deny that Misako’s association with water didn’t come to mean something. After all, when Misako threatens Hanada after his initial sexual advances and he demands rice from her instead, there is a shot of falling water that slowly changes focus so that the water disappears and only her smiling face is left on the screen. Now that she knows that she is in complete control because of Hanada’s thinly veiled demands for “rice,” the positive associations that the rain and water had are gone, not to be seen again in the entire movie save for a brief instant when Hanada leaves Misako. In the same shot where the water fades away, Misako’s face fades to black and is replaced by her next, more sinister main symbol: a butterfly.

The first butterfly we see is the one that lands on Hanada’s gun which causes him to bungle the hit that Misako hired him for. If Misako was the catalyst for Hanada’s downfall, the butterfly was the thing that tipped the scales out of his favor. When Hanada enters Misako’s apartment, he finds the walls covered in hundreds of dead butterflies. Hanada seems more annoyed than shaken by Misako’s choice of interior design, offhandedly noting that it feels like a graveyard in her apartment. When she wonders out loud where she’ll pin Hanada though, Misako manages to get a rise out of him, manipulating Hanada in the way she already knows she can. Misako had stated her desire for death from the very first time Hanada spoke to her, and seeing her obsession with dead butterflies, and a few dead birds, drives the point home in a beautifully creepy way. The butterfly represents death, or at least the threat and promise of death.

As the sequence in Misako’s apartment comes to a close, all of Misako’s symbols and all of Suzuki’s use of dreamlike filmmaking techniques come into play. Hanada says “goodbye” to Misako and leaves her for the last time. He has had his way with her, but he wasn’t satisfied. If anything, his time with Misako made his situation worse. Prior to their rendezvous, Hanada held Misako as a beautiful symbol of something better. He would hear water falling as he thought of her and smelled boiling rice. But she never gave him any rice, and the water didn’t wash away his troubles. Instead, Hanada is left feeling like a failure because his obsession for her not only prevented him from killing her like any good killer would have done, but at the same time it prevented him from giving Misako the death that she so dearly wanted. He failed both of them, and his failures have started to drive him over the edge. As he walks away from Misako, he begins to see images of birds, butterflies, and water as they are plastered across the screen. Hanada becomes more and more agitated as the images increasingly encroach on his space within the frame until his face is completely covered by a butterfly. He is overcome. The scene then cuts to Hanada passed out on the side of a road. He’s hit a new low, but it’s only the first part of his downward spiral.

After taking a deeper look at some of the methods behind the stylistic madness of Branded to KillI, it starts to become clear that this film does not defy explanation. Truly, seeing as how Suzuki Seijun himself has provided different explanations for the film that he made, it’s simply that Branded to Kill’s focus on style over formulaic B-movie tropes means that it is open to multiple explanations. Perhaps if Suzuki’s superiors at Nikkatsu had taken the time to give his movies a fair assessment then they would have found that rather than being incomprehensible, Branded to Kill works on many different levels and can have multiple meanings for multiple people.

Works Cited

[1] “An Interview with BRANDED TO KILL Director Seijun Suzuki (1997).” Interview. The Seventh Art. Daylight on Mars Pictures, 15 Aug. 2010. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.

[2] “An Interview with Suzuki Seijun: Director of Tokyo Drifter.” Interview.YouTube. N.p., 20 Sept 2015. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.

[3] Desjardins, Chris. “Seijun Suzuki.” Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I.B. Tauris, 2005. 147. Print.

[4] Melin, Eric. “‘BRANDED TO KILL’ AN ABSURD YAKUZA DELIGHT ON CRITERION BLU-RAY.” Scene Stealers. Scene-Stealers.com, 5 Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.

[5] Zorn, John. “Branded to Kill.” The Criterion Collection. The Criterion Collection, 22 Feb. 1999. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.